I will confess that I have a strong predilection for the works of the late Austrian writer Gert Jonke. The opportunity to wax on about his gifts in an open forum led me into dangerous territory: do I unabashedly demand that Awakening to the Great Sleep War win your heart solely on my enthusiasm or do I try to pragmatically and logically lay out the novel’s superior strengths based on an unbiased literary perspective? I know I should do the latter, but the problem is that his gifts are so unique and particular that his work really defies logic. If you are the type of reader that can wholly surrender your logic and reason to the absurd and surreal fictional worlds Jonke creates, then you will end up loving him as I do and eschewing attempts at critical pragmatism and decorum. You, too, will rant like a literary lunatic when anyone questions his originality or place in the canon of world literature.

Awakening to the Great Sleep War does not have a traditional plot or narrative. None of Jonke’s works are known for their adherence to the basic tenets of story. He is no Robert McKee. In “normal” Jonke works, a character is introduced into an abstract world that can lead the reader in endless philosophical and metaphysical offshoots that give the reader pause to discover their own imagination. In this novel, Burgmüller is the character through which we experience the surreal experience of time, space, love, and the city. An “acoustical decorator,” he begins the novel by trying to teach the telemones how to sleep since they have held up buildings for so long, surely they must be tired.

As ridiculous as this may sound, Jonke somehow manages to impart a sense of empathy to the reader for an inanimate object and the job of architecture in general. When discovers that the building with the telemones is gone one day, Burgmüller considers the possibilities before he arrives the conclusion that his efforts could have been useful:

Or had they, in his absence, learned how to sleep after all-had they gotten tired at last, as sleepy as petrified darkness pulled in toward the center of the earth when the trap doors to the planet’s cellar began to open?

Awakening to the Great Sleep War, Gert Jonke

That’s a reason this novel should win in my opinion. How many authors can pull that off?

Never fear, traditionalists; there is a love story amongst the surreal renderings of our dear Jonke. There are two love stories of the classic sort — man loves woman, she leaves; man loves another woman, she too leaves. Then there is the lesser-known love story between a woman and a housefly named Elvira. But regardless of who loves whom, the love is as poetic and mournful as any other love story, as Jonke displays in Burgmüller’s girlfriend’s plea to love the housefly as she does:

But the most important thing at present, she continued, was to give Elvira a chance to rest, not to frighten her in any way, above all not to make an unnecessary noise, you know, people talk much too loudly, as she was now noticing, and if he would please just put himself in the position of the housefly; just imagine, she explained, if that huge building over there across the way suddenly started a conversation with the church tower behind it, can you imagine how loud their words would sound to you, you would thin the tall building or the church yelling at you, or that they were screaming at each other, do you understand what I mean, and when we talk with each other, it must seem about that loud to Elvira, in future we have to talk much more quietly, better yet, whisper, do you understand, nothing above a whisper!

Burgmüller loves this woman and feels he must love Elvira as much to prove his love for her. It’s one thing to explore the love relationship between a woman and a housefly, but to do it with a blend of humor and poignancy is rarely done in adult literature and done successfully.

Through the rest of the novel, Jonke examines the vicissitudes of love with another doomed love affair. Burgmüller falls for a writer who views her typewriter as a “reality-producing projector.” Within one paragraph, the invisible line between reality and art as a reflection of reality is woven into her struggle as an artist to perfectly represent reality and how this struggle affects their relationship:

Unflustered, she crouched at her typewriter, into which she transmitted her tapped signals as usual long into the night, continuing to work on her world, in which her eyes now became a compass rose torn by its own magnetic needle, cut up by the letters of a white-hot cuneiform script, yes, a cuneiform script of the harbor cities that reproduced themselves incisively upon all the coasts with their power-saw boats, in the service of an endless alphabet, like a science without proofs, until the morning flickered like fire from the towers, all of which crossed her lips as usual, whispered in a low voice, while she was sitting at her typewriter as if at a steamship propelled by sewing machines, floating, drifting downstream in the room, midstream in her description, from which he could now hear something about cats with heads like ants, and palm trees with crayfish living in their branches, but that could also have had to do with an entirely different chapter of her story that had crushed on ahead, considering her work tempo he never know how far ahead of him she was at any given time.

Jonke tackles the philosophical questions of literature and art and how the artist struggles between the importance of the word and the importance of what the word represents. Can anyone ever really love in a reality like that? These are questions not often asked to the reader, but nonetheless are always present in the relationship between the writer and the reader. No other novel on the long list challenges us in this way.

A novice translator could easily have mishandled all of Jonke’s absurd, surreal concepts and themes, but Ms. Snook understands the nuance in Jonke’s text to convey the aims of his novel. With a traditional narrative and story structure, it is easier to be more loyal to the text and more literal. In this case, the translator must also understand the abstract concepts and how to put those conceptual ideas in play without sacrificing the wit of Jonke’s style. Thus, this seems one of the most challenging efforts as far as translation is concerned because the translation must carry through thematically as opposed to carrying the story through a conventional structure. Each word holds more weight so that the subtext is present. To have such intimate knowledge of the writer’s work as well as the language clearly makes this novel the strongest translation on the list.

Finally, there is the simple fact that Jonke’s lyrical language paired with his post-modern themes makes for the most distinctive voice make him a novelist who was ahead of his time. He created a body of work so magical, original, and insightful and this gem solidly establishes him as an overlooked voice in Austria’s literary history. Then again, I am in love with Jonke and always will be. And that is lOve with a capital O which is as close to Jonke and love as one can get.

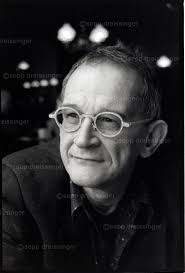

Gert Jonke is counted among Austria’s most important authors and dramatists. Among other prizes, he received the Ingeborg Bachmann Prize, the Erich Fried Prize, and the Grand Austrian State Prize for Literature. He died in 2009 at the age of 62.